When Middle Schoolers Can’t Read: Let the Data Lead Your Inquiry

Their reading scores were hard to believe. The 6th-grade students who sat in front of me–Arelcy, Edvin, Julian, and twins Antonio and Ernesto*–were excellent students. They had good attendance, attention, behavior, and effort, but, according to the scores I was looking at, they couldn’t read.

It couldn’t be true. The test scores must be wrong, I thought. Maybe they weren’t trying or perhaps they had a bad test day. It was September 2017, the very beginning of their first year of middle school. Not knowing much about them yet, I knew I needed more information, so I listened to them try the simplest text I had in my test set and I had to admit it was true: they could not read.

When it became undeniable that five great students had not yet been taught to read in elementary school, it was my job to do something–after all, I was the school’s reading specialist–I just didn’t know what it was. I was supposed to be the expert at my school, but I wasn’t prepared for this. “Sound it out” was nonsense to students who didn’t know the sounds. “Slow down and focus” was ridiculous advice to students who couldn’t begin. “Read more”? They couldn’t read at all.

Already in the classroom for more than a decade, most of my work had been at the high school level teaching Humanities. Over time, I realized that it was not just that students didn’t enjoy reading, many of them could not read with ease or confidence. I became certified as a reading specialist and found my way to middle school to address the issue. I had been teaching reading for a few years and saw good results with some students as they read more, were given strategies for comprehension, and provided attention and time to read. Yet, I was troubled by the students who worked hard but didn’t seem to progress. These were the 6th-grade students I had in front of me.

This group of students forced me to confront the unpleasant truth that what we offered in terms of a reading program wasn’t appropriate or sufficient for some students; specifically, the ones who struggled the most.

Guided by Curiosity

I tried tweaking what I was doing, borrowing a lower level of the same curriculum from a teacher friend at another school. It didn’t work: students were still not reading accurately or fluently and their comprehension had big holes. The books were shorter and easier, but still a guessing game for these students. I talked to everyone I knew in reading instruction, I spent time on the Internet and in my books. I listened to my sweet 6th grade students try to read and I listened to them explain what it felt like for them to read, so my search was directed by data. In partnership with Lead by Learning, the English department began meeting monthly to engage in inquiry and research about our classroom instruction to support literacy. I used this as an opportunity to confront the truth that what I had been doing didn’t work for all students and to become curious about what could work. I was working with the invaluable Jennifer Ahn, and she encouraged me to keep asking questions and believe what students were telling me. This led me to an idea.

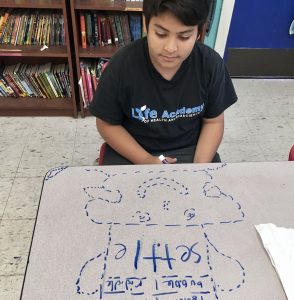

Edvin is in 6th Grade, learning consonant -le syllables.

Based on listening to them read, I thought the students might need to learn the sounds that letters made. At first, this sounded crazy to me: they were in middle school–of course, they knew their letter sounds! But my “tweaks” weren’t working for these lovely kids, so I need to try something completely different. I found a dusty box buried in the copy room on a back shelf. It was a phonics program based on Orton-Gillingham methods and I started using it with the kids.

While comprehension data initially showed no progress, my on-the-ground data showed otherwise. They were slowly learning the relationship between sounds and letters and were able to read decodable texts that employed sound-spelling relationships they had mastered. The phonics program was working, just so slowly that I couldn’t perceive it using my usual measures, which were based on comprehension. They were learning to read, from the very beginning, so comprehension-based assessments didn’t detect the real movement they were making in learning sounds and blending them together into words: the foundation of reading.

I can’t say they learned to read overnight, but using focal student interviews, Learning Partnership Conversations, and listening to what students were saying (with the help of my Lead by Learning coach and through the vehicle of Public Learning) I began to think that the new program was the right approach. Soon it began to show in external, traditional data. These bright kids began to look forward to taking the Reading Inventory (RI), which we did three times each year because they knew their scores would go up–and they did.

Arelcy’s RI scores (2013-2023)

Edvin’s RI scores (2014-2023)

Meeting our Indicators of Success

These five students are now seniors about to graduate high school. Arelcy chose to be a reading tutor for her junior year internship and will soon present with me at a reading conference about her path to literacy. Edvin was recently reclassified as English Fluent. Ernesto and Antonio still struggle with reading and will for their whole lives. They have dyslexia and it will always impact their ability to navigate the written word. Julian, no longer my student, texted me to share that his RI score in 10th grade was on grade level, so we could celebrate together.

He had done it. He learned to read. Our school taught him to read when he hadn’t been taught for seven years of elementary school. It hadn’t been easy for me to squarely face the fact that what I had been doing wasn’t the right thing for these students. It wasn’t easy for the students to spend 45 minutes each day doing something that has been a source of failure throughout their educational life. But we had kept at it, following the data where it led. We know the statistics for kids who can’t read. But no one knows the unlimited possibilities of students who figure out how to make it through elementary without literacy and then snatch up the opportunity to learn to read when they get it. Now, as these students finish high school and move forward with their lives, we will get to see.

The Impact of Inquiry

I credit Lead by Learning for equipping me with the tools to look squarely at hard data. To help me not turn away from it, but to become curious. With an inquiry stance and the support and encouragement of Jennifer Ahn and my team, I was able to figure out the next steps and to know when I needed to change direction and when to keep stepping. We worked, we looked at data, and then we worked some more: sometimes changing direction, sometimes giving more time and practice to the thing we were doing. This reliance on data, particularly focal student interviews where we talk to students about their experience as we tried new things, was radical, gnarly, difficult, and ultimately very fruitful for these five students and far beyond.

The reverberations of what we learned from that group of young people shook the foundations of our entire school’s reading program. We abandoned the disproven methods we had been using and completely reimagined how to teach reading:

- Putting accuracy and fluency first,

- Developing language skills, and

- Building background knowledge.

Our school’s reading program now follows the principles of the science of reading and reaches 100% of students in Grades 6-10. The literacy department is composed of thirteen teachers, most of whom also teach core classes and two full-time reading interventionists. The progress made by Arelcy, Julian, Antonio, Ernesto, and Edvin is no longer considered exceptional, but one we know all students can make. We’ve created a system that looks at student data and responds to it. By putting student data in a starring role and shining a relentless spotlight on their experience, we were compelled to stop doing what was familiar and comfortable, but not beneficial, and instead changed our practice to do what our students need and deserve.

Letting the data lead us into new places has become our reading program’s refrain as we continually work to improve offerings for our students. Now, all incoming 6th graders and new-to-Life Academy students in other grades are given an accuracy/fluency reading test and potential phonics follow-up within the first week they arrive at our school. We use the data to program students into reading classes based exactly on their needs. Some students need to start with letters and sounds and we have a program ready to teach them: we refuse to pretend they know how to read if they don’t. As students grow as readers–information we know because we now regularly look at multiple data sources, including the iReady, DIBELS, and phonics inventories–they move into different classes to take them to the next level. There were many difficulties along the way to making a universal reading program in our middle school and–believe!–there are still many complications about scheduling, training, and curriculum. The work will never be done, and it will always be worth it. As we continually self-interrogate our practice based on student outcomes, I take inspiration from author Ghouldy Muhammad when she said, “We’re trying to help our students leave our schools and make the world a better place. We cannot keep repeating the same history.” Literacy skills are the foundation for academic success and community participation. Let’s change history. Let’s equip our students with reading skills they can use to make a better world.

*Changed names for student confidentiality

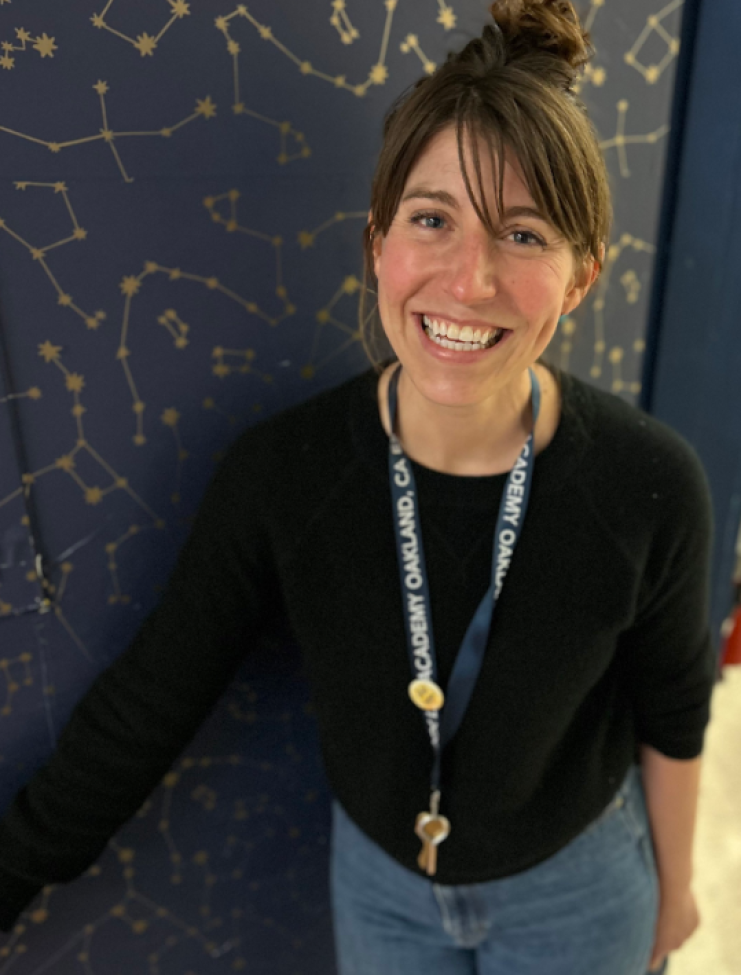

Christi Grossman has been a teacher for over 20 years. She started teaching in a small community in Ethiopia, then worked as a high school English teacher in Detroit before moving to Oakland. Life Academy has been home since 2014 and she delights in continuing to build a school community that supports students in reaching their dreams. At school, Ms. Grossman can be heard singing in the hallway and seen chasing students down for permission slips. Ms. Grossman’s passion is books and she loves to turn reluctant readers into skilled, eager ones.

Christi Grossman has been a teacher for over 20 years. She started teaching in a small community in Ethiopia, then worked as a high school English teacher in Detroit before moving to Oakland. Life Academy has been home since 2014 and she delights in continuing to build a school community that supports students in reaching their dreams. At school, Ms. Grossman can be heard singing in the hallway and seen chasing students down for permission slips. Ms. Grossman’s passion is books and she loves to turn reluctant readers into skilled, eager ones.