Teaching Language in the Science Classroom

As the last bell rang and the students rushed out of the front gates, I wandered into Zander’s classroom to process our days. We teach different subjects at our public high school in Oakland Unified School District, he, World History, and myself, Chemistry, but we have the same students in our classes and we both spend time thinking about how to develop students’ language skills.

On this day, early on in the second semester, students were developing their written explanations of what happened during the flame test lab–an experiment that involves heating up various ionic compounds in a flame and observing the color that is produced. After performing the experiment and synthesizing ideas from various scientific models, students were ready to begin their writing. My goal for this assignment was to find structures that support students in bringing specificity to their writing. Throughout the first semester of school, I noticed that the majority of my students were vague in their writing–they used the word, “it”… A LOT!

I had the opportunity to investigate how to support students in bringing specificity to their writing through a professional development series put on in collaboration between OUSD’s English Language Learner and Multilingual Achievement Office and Lead by Learning. In this space, I was able to process how to integrate instruction on student talk and student writing in my classroom. Then with Zander, who had done this professional development the year before, I polished my ideas and clarified what I wanted to try in my classroom.

I decided to start by addressing vocabulary use. After having students discuss and then write about the process of luminescence, I projected a model labeled with key vocabulary words that students were familiar with. Their goal now was to rewrite their explanations using at least five vocabulary words. During class, I noticed that students seemed to be able to do this task quite easily and accurately, which gave me the impression that they understood the vocabulary and the concepts. It was my hope that by setting aside time for revising their writing with an emphasis on including tier three vocabulary, students would be able to recognize that they could use these terms to add strength and specificity to their writing.

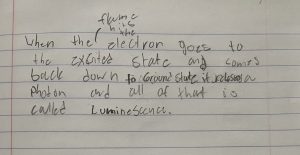

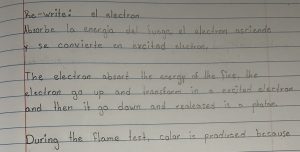

At the end of the school day, I brought Zander some student work samples, eager to show him how students had incorporated tier three vocabulary into their writing. We selected some focal students who were English Language Learners (ELLs) and looked at their writing to see what improvements they had made (Figure 1). While they were able to incorporate many vocabulary words, their writing was much shorter and less detailed than students who are not classified as ELLs. As Zander and I pieced apart different students’ writing, he began to notice that the most successful students not only had an understanding of the vocabulary, but they were also making complex language moves. For example, many students explained luminescence as a process, using sequencing terms like first, next, this causes, etc. This left me with a new goal–in addition to emphasizing scientific vocabulary, I planned to teach students (or remind them of) a language move that would support their next piece of writing.

Figure 1: Student writing samples from their explanations of the flame test lab.

Student 1: This student incorporated the words electron, excited state, ground state, and luminescence.

Student 2: This student began his thinking process in Spanish, his home language. He then switched to English and expanded upon his original thoughts in Spanish.

In their next writing assignment, students were tasked with explaining a model of an atom and a molecule and then used both models to explain how bonding works. My goal was for students to be able to explain a visual model in writing, so I needed them to incorporate prepositional phrases, the language move, into their response in order to point the reader’s attention to a specific part of the model (for example, in the center, on the outside, etc.).

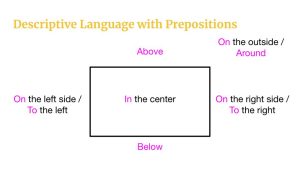

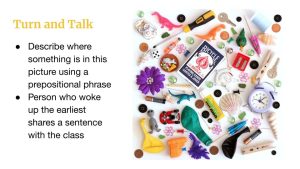

To introduce the assignment, I instructed students to write about a Bohr Model of an oxygen atom using a certain number of scientific vocabulary words. Then, I introduced the language move that I wanted students to use in their writing. I gave students a bank of prepositional phrases that I thought would be helpful (Figure 2), and we practiced using the phrases in a non-scientific context (Figure 3). Finally, I had students re-write their original explanation and incorporate these prepositional phrases.

Figure 2: The prepositional phrase bank for students to reference throughout their writing process. There is a visual element of this phrase bank to support ELLs.

Figure 3: A slide with instructions for the student talk activity to practice using prepositional phrases. A response could look something like, “The purple clock is above the seashell,” or, “The purple clock is on the right side of the image.”

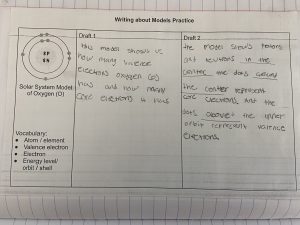

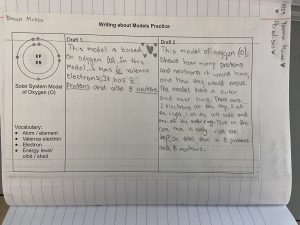

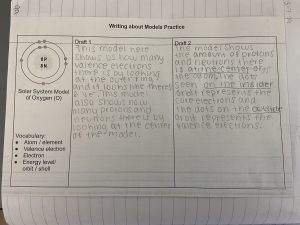

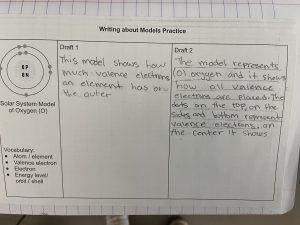

This time, as Zander and I looked over students’ writing, we noticed that students used prepositional phrases to expand and add clarity to their explanations (Figure 4). For example, Student 1 is able to be more specific about core electrons versus valence electrons, and they add more details about the nucleus. Meanwhile, student 3 was already using prepositional phrases in their first draft; however, in their second draft, they seemed to make their words count a little more. Their first sentence in draft one is long and repetitive, and in the second draft, they get to the point much faster. Student 2’s writing is interesting to look at because in some ways their second draft actually became more confusing. They decided to use prepositional phrases to zoom in on the placement of each individual electron, and while this isn’t necessary, it does show that this student has a solid handle on prepositional phrases!

Figure 4: Student writing samples from the atomic model in-class writing activity. All work below was written by ELLs.

Student 1

Student 2

Student 3

Student 4

I walked away from this activity feeling quite proud. Students, for the most part, were able to dramatically improve their writing after just twenty minutes of talking about prepositional phrases. Throughout this activity, I did not provide any sentence starters. Instead, I scaffolded the writing process by giving students a specific language move to implement, and all of my students were able to apply this to their writing, including English Language Learners and Newcomer students. When it came to drafting their graded response, some students slipped back into old habits and did not incorporate the language move into their writing, so my goal for next year is to continue building systems and rubrics that support students throughout the entire writing process instead of just in the beginning.

I am leaving this school year feeling pleasantly surprised that small but targeted instructional changes can lead to such dramatic results. As I have learned in Lead by Learning and in short conversations with Zander after school, it takes about ten minutes to scan student work and analyze language use, but this goes a long way in informing how I approach scaffolding writing assignments. I am looking forward to continuing to experiment with language instruction in the science classroom and seeing the impact that it has on my student’s ability to meaningfully communicate scientific concepts and results.

Sam is a chemistry teacher at Madison Park Academy in Oakland, CA. She received her B.A. in Biology and Anthropology from Washington University in St. Louis and her M.A. and teaching credential from the University of California, Berkeley. In the classroom, Sam values the connections that she makes with her students, and she aims to use science to develop student’s critical thinking skills.

Sam is a chemistry teacher at Madison Park Academy in Oakland, CA. She received her B.A. in Biology and Anthropology from Washington University in St. Louis and her M.A. and teaching credential from the University of California, Berkeley. In the classroom, Sam values the connections that she makes with her students, and she aims to use science to develop student’s critical thinking skills.

Interested in working with Lead by Learning to support professional learning for your staff? Connect with a member of our team to learn more about our partnerships.