Developing a Teacher-Leader: The Importance of Self-Efficacy, Flexibility, and Collaboration

This past school year brought many changes to my role on campus. As the ELA intervention coordinator at Dublin High School, I took a department-wide approach in addressing student learning needs through tiered supports: identifying strong teaching practices to support all students, implementing small group instruction, and placing students in a more intensive program to accelerate literacy needs. Prior to this, I was always inclined towards inquiry and always sought to learn more. Seeking to understand rather than to solve situations is what led me to choose a focus question to guide all inquiry this year, that question is:

How can I use my role as an intervention coordinator to illuminate struggles, address challenges in learning, and collect data?

As I wrapped up my sixth year of teaching at Dublin, I found that my leadership was very much part of Dublin High’s progress to differentiate and support learning, for both students and teachers alike. This really fits into the PLC, Professional Learning Community, changes we’ve made this year to create systemic changes in how we implement and select interventions that are effective and equitable for our students who have diverse needs. To better contextualize the approach, it is important for me to highlight Dublin High’s umbrella goal:

PLCs at Dublin High School will use student data to increase learning and disrupt inequitable practices and interrogate biases to create a safe and productive learning environment for all students, especially for our students from historically marginalized communities.

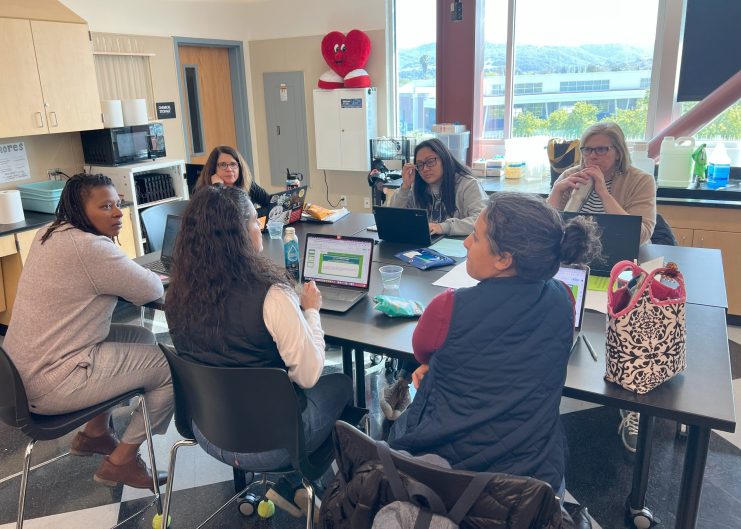

While our inquiry team meetings centered around this goal, our PLCs themselves needed additional support in gathering the needed data to examine how their students were progressing. I focused my work on collecting and analyzing student data across ELA classrooms and grade-levels. However, in my delve into student data, I determined that I should look at street data and other factors that contribute to student learning because I was so curious about so many possibilities related to why particular students were still struggling to meet learning outcomes in summative assessments, and what teachers have tried to support these students. Attendance rates, standardized test scores, incidents, accommodations/needs, demographics, and anecdotes from teachers were all included in an Excel spreadsheet. I created tabs for each teacher and hid student names and then created a summary tab that was shared with PLCs to identify patterns and engage in data talks. I was curious about so many things at the same time when it came to what was working and what wasn’t in classrooms, and how non-academic factors impact how students fare on the success criteria used to judge successful learning.

My method revolved around systems thinking and determining what we have in place and need to have in place to guarantee access to learning. Part of this is also using data as a tool to disrupt our own biases and what we think we know about students and teaching. One clear moment that was most impactful for me occurred while discussing the results for each PLC’s common formative assessment. My bias was inherent in my assumption that we were all aligned in our progress toward equity. I found out that our definition of common assessments, grade-level texts, rubrics, success criteria, and even the number of progress assignments to prepare for a common assessment varied. I had to pause and figure out how I would address this conundrum.

What I found was that the results of learning that we, as PLCs, use to collectively judge how successful our students are performing can be distorted by variances that we create in our own classroom environments. Its not to say that we shouldn’t adapt to our students’ needs, but rather, the process we are engaging in to determine how students are progressing toward the essential standards of the course must be consistent in how we assess ALL students. So while we are looking at letter grades or percentages on how students are meeting specific skills or standards, we also have to make sure that the materials, assessment questions, and even our grading is calibrated to make sure that we have the same criteria in which we collect data to make instructional decisions. In the summer and at the start of the next school year, we will be taking this reflection and using it to inform needed changes in our scope and sequences.

Now that I have had some time to reflect back on our progress this school year, I believe we have enough momentum to work toward creating, implementing, and measuring how we orient our grading as a team. This year was about getting our feet wet, asking questions as we acclimate to new changes, and trying something different. The most impactful part of it all is the continued collaboration and ownership my colleagues have in this process. One of the most important takeaways for me as a teacher-leader is that to build agency in adult learners is to create a collaborative space that encourages questioning and adapting.

Ramany Kaplan has been in the classroom for 9 out of 16 years in education. True to her mantra that as a teacher she is a life-long learner, she earned an English MAT at USC in 2015, an M.S. in Reading and Literacy Leadership at CSU Fullerton just a few months ago, and is currently researching doctorate programs. Acts of service is her love language and she loves working at DUSD’s Dublin High School, so much so that she is currently an English Department Co-Chair, ELA intervention coordinator, advisor for the school newspaper, and member of the Lead By Learning Design Team. She enjoys the great outdoors and loves gardening, camping, hiking, and people watching.

Ramany Kaplan has been in the classroom for 9 out of 16 years in education. True to her mantra that as a teacher she is a life-long learner, she earned an English MAT at USC in 2015, an M.S. in Reading and Literacy Leadership at CSU Fullerton just a few months ago, and is currently researching doctorate programs. Acts of service is her love language and she loves working at DUSD’s Dublin High School, so much so that she is currently an English Department Co-Chair, ELA intervention coordinator, advisor for the school newspaper, and member of the Lead By Learning Design Team. She enjoys the great outdoors and loves gardening, camping, hiking, and people watching.