The Power of Prioritizing Student Voice

Our relationship with writing can color our entire experience as a student. It can give us the confidence to tell our story and to use the depth of language to express what we know. But if we never build the confidence to take risks, it might paralyze us with self doubt.

I used to be afraid that if my students became confused or insecure about writing, they would give up and disengage from it. I wanted writing tasks to be as clear as possible, so everyone would participate. I assumed that being a good teacher meant 100% participation and that active participation was synonymous with success. So I made assignments to be foolproof, in hopes that students would engage and feel successful.

An example of this was when I asked students to answer identical essay prompts using an outline with sentence starters for every sentence of the essay. Like I intended, everyone submitted their essay, which felt like a victory until I began grading and discovered that every essay was the same! Every analysis, the same. Even the textual evidence they chose was the same. It was disheartening to read over 100 papers that were almost identical in content. In my naive effort to prioritize participation, I had inadvertently taken away the opportunity for students to make meaningful connections to the text and develop their own distinct writing voice.

Returning from distance learning, I reflected on my mistake and decided that I needed to focus my practice on elevating student voice. This was especially important for supporting the academic growth of my Long Term English Learners (LTELs), whose only writing instruction for the last year was on zoom. In order to give myself a structured learning environment to brainstorm ideas and hold myself accountable to meeting my goals, I joined the ELLMA inquiry community Lead by Learning. In this space I was challenged to think critically about what language instruction was necessary for strong writing and what changes needed to be made to reach a high caliber textual analysis by the end of the year.

After a year of distance learning, students needed daily opportunities for discussion. Generating and listening to ideas was also a great way to process information and prepare students for writing. We started each day with a low stakes reflection, followed by a partner and whole class discussion on the topic. This routine legitimized a wide range of possible answers for a single prompt. With my goal in mind, our first essay of the year focused on the technical skills and organization necessary for essay writing, but after laying this foundation, I shifted to prioritizing the construction of a strong analysis. Afterall, technical writing isn’t a prerequisite to higher level thinking, which is ultimately what I hope students achieve from being in my class. Each assignment needed to bring us closer to a claim that could be vehemently argued with a thoughtful analysis.

Prior to our second essay, which focused on the Harlem Renaissance, I wanted students to make meaningful connections to the powerful poems, songs, and short stories we were reading. This meant taking the time to ask them what they were taking away, instead of telling them what to take away.

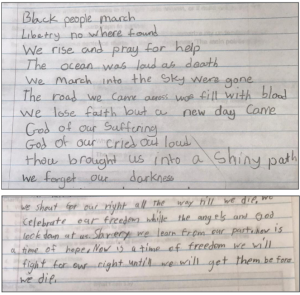

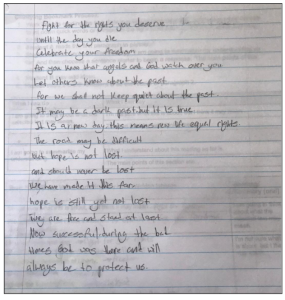

First we annotated chunks of the text as a class, next we collectively brainstormed the meaning of the figurative language, and lastly, I asked students to discuss what possible themes were evident to them. Each idea was shared with a partner and then with the class. Once students heard from each other, I asked them to try to rewrite the poem in their own words while considering our class discussion about the theme. I reminded them that everyone’s work would be different because everyone has their own vocabulary and distinct writing voice. Below are three rewrites of James Weldon Johnson’s Lift Every Voice and Sing by LTEL students in my ELD-d class.

With minimal support, they successfully identified and described the underlying themes of a perplexing 100-year-old text. The benefit of giving students the agency to use their own authentic language to express themselves was clear in the rewrites they produced. Rather than using a language objective that limited the scope of their analysis, I elevated the comprehension of the word “theme.” Whether their poems stayed true to the original theme of Lift Every Voice and Sing, would determine if they met the language objective or not. I found that the words that we instinctively associate with a specific idea can be a bridge to developing a deeper understanding of a complex text. However in order to build this bridge, our class needed to be a space where all ideas could be heard and validated. It needed to be safe to take risks, even amid moments of self doubt.

Me: “What do you think they mean by ‘Lift every voice and sing’? What does that mean?”

Student A: “…Speak out?”

Student B: “…Lift each other up?”

Student C: “…Use your voice?”

Me: “Excellent! (validates by annotating the ideas onto the text)

What about ‘Till Earth and heaven ring’? They should continue to do this until what?

Student A: “Until they die…?”

Me: “What if I add ‘Ring with the harmonies of liberty’? What is liberty?

Student B: “Until there is freedom…?”

Me: “Exactly!”

According to the curriculum, our next step was to work toward answering the essay question: “How do the works from the Harlem Renaissance convey the theme that collaboration and community bring out the best in us?” The prompt gave them the theme with which to write about. From experience, I knew students would likely choose the same obvious works to pull evidence from and as a result reach the same conclusions. This is exactly what I wanted to avoid: the diminishment of original ideas and authentic connections. So, I altered the prompt to require students to do more of the lifting and allow for a more purposeful analysis. In the end, I asked students to answer the question “What is the most compelling theme collectively conveyed by the works from the Harlem Renaissance?”

To begin building our claims we brainstormed a list of themes present in the work from the Harlem Renaissance. For example: family is an important source for support (Paul Lawrence Dunbar), you can find strength by looking to the past (Langston Hughes), or don’t lose hope because dark times won’t last (Georgia Douglas Johnson). Students could pull from the class list, or come up with their own theme to answer the prompt. As a result, students generated diverse evidence based claims and demonstrated powerful textual analysis in defense of their writing choices. They pulled from vocabulary we brainstormed as a class but also included their own theories and connections about the underlying lessons found within the Harlem Renaissance. It was so gratifying to read their final drafts and recognize the ways in which students were distinguishing themselves in their writing. Having the freedom to build their own argument and choose their own evidentiary works challenged them to dive deeper into the texts and use independent research to find the precise vocabulary to describe their ideas. They were not confined to their scaffolds and had the autonomy to go further and deeper into their analysis.

After completing the school year, I was informed that over 50% of my English Language Learners scored the highest score possible on the English Language Proficiency Assessments for California (ELPAC). The greatest value of evaluating the quality of student work early in my career was the insight it gave me into my own practice. I was able to unravel the important difference between providing students with structure and demanding excessive control over student output. This realization was especially pertinent for my multilingual students whose mastery of English calls for authenticity and self direction. If our goal is to develop critical thinkers, then students need the opportunity to learn by way of self exploration. Faced with the unknown, our instincts become our guide and we can always build from what we already know. These first initial steps in the learning process deserve praise and validation and have the potential to become a powerful written analysis.

Although many things advanced the academic growth of my students, an important contributing factor was embracing a change in mindset on how to support their writing. To recap I have learned to:

- Practice asking students to put anchor texts in their own words

- Create class generated word walls of ideas students associate with the topic

- Write prompts in a way that gives students choice in how to respond

Julie Mendoza has taught Humanities at Roosevelt Middle School since 2018 and served as the Humanities Department Chair from 2021-22. She has a Masters Degree in Urban Education from Loyola Marymount University and in Fall of 2022, began her first year as a law student at U.C Hastings. Born and raised in the Bay Area, she is passionate about social justice and public service. On the weekends, she can usually be found hiking in the redwoods with her dog and husband or gardening at her home in East Oakland.

Julie Mendoza has taught Humanities at Roosevelt Middle School since 2018 and served as the Humanities Department Chair from 2021-22. She has a Masters Degree in Urban Education from Loyola Marymount University and in Fall of 2022, began her first year as a law student at U.C Hastings. Born and raised in the Bay Area, she is passionate about social justice and public service. On the weekends, she can usually be found hiking in the redwoods with her dog and husband or gardening at her home in East Oakland.