Literacy Over Mastery: Adjusting my Priorities as a Leader

An Uncertain Return

Summer readings for professional development always appear exciting at first — there is so much hope and promise for change and innovation in that nascent stage of planning. And throughout our extended year of distance learning, our entire school district was trained on how to flip our understanding of grades and assessment; it was clear that our ties to an outdated and unfair model that prizes points over learning should be replaced with something better. So, as I read Grading for Equity, a series of pulsating questions for my English department became energizing catalysts:

- Do my students understand how to read a rubric?

- Will those rubrics be equitable and accessible for our students?

- Are my teachers invested in pushing towards a mastery-based grading system?

- Can students let go of ideas about extra credit and replace them with motivation to improve and resubmit their work?

I’d been grappling with these questions for years, but now I saw a window for a larger movement beyond my classroom; 2021-2022 was going to be the year of not only a return to the physical classroom, but a return to rigor and holding students accountable to standards. Before we welcomed back students into our classrooms, my colleagues and I agreed that our upperclassmen would earn a final grade purely based on their performance on essays and other major projects.

The months wore on with some hints of success, but December seized our schools, still masked and anxious, classrooms emptying out amid the Omicron surge; my leadership of the De Anza High School English Department entered shaky ground. I had to reconsider everything come January, and so did my school, and a new buzzword “literacy” replaced my dreams of “mastery.”

The Push Back & The Pivot

So what is literacy exactly? Fundamentally? Yes, we are talking about our students’ reading comprehension, but we are also talking about the ability of our educators to make course content accessible; and even more importantly, we are talking about the development of an academic identity from our learners. In this paradigm, mastery of a rubric is subordinate to the understanding of a lesson. Across the content areas in our staff meetings, teachers and administrators were now urgently discussing the “literacy strategies” we could implement together as a site. From this impetus, our department began to pore over student data from a second round of standardized reading assessment data in the winter, and we saw that our students had decreased in proficiency from our first quarter of data collection.

The reality of this push back forced me to confront our learning community with compassion and with grace; we needed a new plan, and I clearly understood that our teachers had more pressing needs than modifying the nature of their gradebooks. Our students needed extensive practice working with tools for reading comprehension, and the almighty crisis of finding a purpose for school itself was more relevant than ever; this was not the year of the rubric. With this in mind, I sought counsel from trusted colleagues in the department — two of which were already working as members of a “Literacy Team” — and I embraced the Lead by Learning model to take a step back from the intellectual ambitions of August and ground myself in the practice of Public Learning, as a listener and a facilitator.

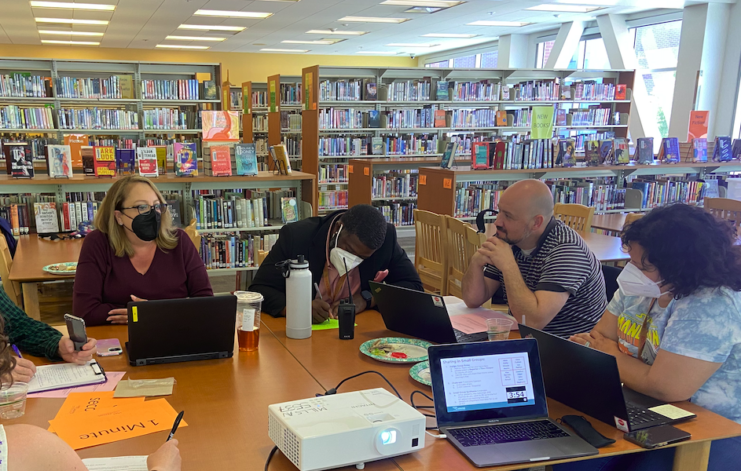

In two or three strategic one-on-one meetings with my focal group of teachers, we made a plan for using our department meeting time as an opportunity for an open-ended analysis of student work. We would share, but we would not feel the need to calibrate the essays on a rubric and get into the weeds about all those finer points regarding grammar, structure, and citation. We talked about emerging trends in small grade level teams and identified one common “literacy” strategy per team, such as the use of graphic organizers to show reading comprehension. My team felt heard with this pivot, and we got to work in the spring sharing resources around a small and manageable goal: give students improved access to our content so they can better identify with what they are reading and writing about.

Moving into the final quarter of the school year, I followed up about the implementation of our common literacy strategies with a tenacious first-year English teacher. She expressed new feelings of comfort coming to meetings discussing and sharing her own student work. All the emotional tension bubbling up during the first half of the school year, arguing with students about how they were graded in her classroom, gave way to extended tutoring sessions where she was able to find ways to differentiate the graphic organizers for different levels of readers. Her students may not have reached higher scores on a standardized test, but she was reaching more of them in a more meaningful exchange of learning. Literacy over mastery.

A New Vision

In the post pandemic age of educational leadership, we must start to tell a story about our priorities, about listening and knowing when to shift our focus as leaders. We can only collect so much data of dissension and learning loss before new practices must be initiated, before new narratives about how to reach our students must be forged.

As I step away from four years of leadership as English Department Chair, I look back most fondly on the supportive teamwork and the shared responsibility developed by my colleagues. My shift in focus allowed a department that lost two staff members throughout the school year to find common ground for productive discussion and pathways for direct implementation of improved classroom strategies. My original goal mattered little in the end, and the new goal was just a beginning; so with this foundation, I hope that De Anza’s English Department will:

- Focus on gathering internal reading data based on their own original assessments and graphic organizers

- Read more with their students in the classroom to garner literacy in real time

- Collaborate to make simple realizable goals that can be implemented in small teams before being administered to the entire group

- Continue being more open and vulnerable as fellow humans sharing a common struggle

Nathan Nugent taught English at De Anza High School in Richmond, CA from 2016-2022. A graduate of San Francisco State University’s school of journalism, Nathan traveled and wrote as a cultural reporter before entering Sonoma State University’s Credential program in 2014 to begin his career in education. When not buried in a book or out hiking on another road trip, Nathan spent four years working as English Department Chair leading his colleagues in collaborative inquiry. For the 2022-2023 school year, Nathan has transitioned to full-time graduate study in the department of Rhetoric and Writing Studies at San Diego State University. He has been accepted to begin teaching first-year college composition as a Teaching Associate at SDSU and plans to earn his MA by the spring of 2024.

Nathan Nugent taught English at De Anza High School in Richmond, CA from 2016-2022. A graduate of San Francisco State University’s school of journalism, Nathan traveled and wrote as a cultural reporter before entering Sonoma State University’s Credential program in 2014 to begin his career in education. When not buried in a book or out hiking on another road trip, Nathan spent four years working as English Department Chair leading his colleagues in collaborative inquiry. For the 2022-2023 school year, Nathan has transitioned to full-time graduate study in the department of Rhetoric and Writing Studies at San Diego State University. He has been accepted to begin teaching first-year college composition as a Teaching Associate at SDSU and plans to earn his MA by the spring of 2024.