Increasing Newcomer Student Confidence in Community Circles

A lot can happen over the course of a weekend. Family members come to visit, birthdays are celebrated, pets get sick, little siblings hurt themselves and recover, and there are eventful excursions to the zoo or Chuck E Cheese. In my third grade class, Monday morning is a time when every student has the opportunity to share a “rose” and a “thorn” from their weekend. Some launch into long stories packed with details, while others share short and sweet snippets from their lives outside of school; occasionally a student shares something vulnerable or heavy which prompts a follow-up check-in at recess or after school. But no matter what time of year or what else is scheduled for the day, students excitedly come to the rug for our Monday morning ritual, and listen attentively as their peers share their weekend roses and thorns.

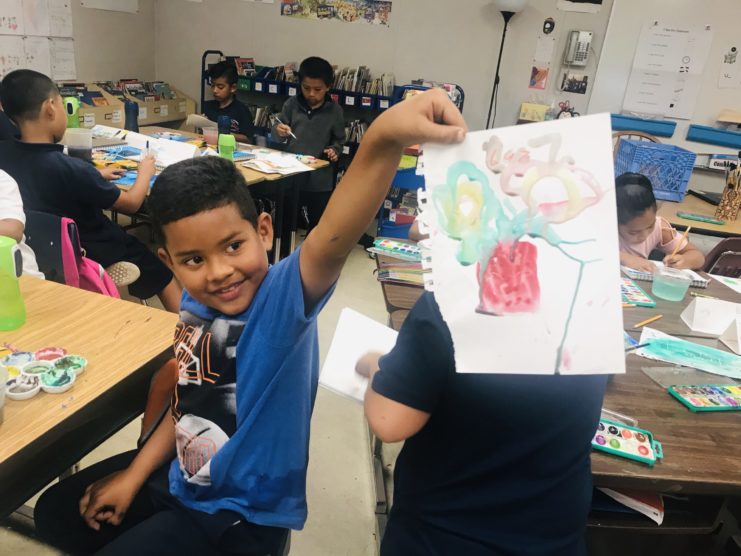

At the beginning of this past school year, I had four students who had moved to the US within the last six months. Each of their parents told me nervously on the first day of school that their child did not understand or speak any English, and I assured them that they would be fine, that they would make friends and feel welcome in our classroom. While all of my newcomer students were quickly able to learn our classroom expectations and easily socialize with their peers, they were understandably timid and withdrawn in whole-class English discussions. One routine that I thought would be a low stakes entry point to whole group participation was our weekly Roses and Thorns Circle. I wanted to support my newcomer students in growing their confidence in the classroom and encourage them to take risks within the safe space of a consistent classroom routine. In order to do this, I needed to identify the language the students would need to participate, and I also wanted them to develop the tools to then transfer those oral shares into writing.

Before I began my inquiry project, I observed that none of my newcomer students shared in community circles. Each time they would shake their head or quietly say, “Pass.” In order to address this, I met with them in a small group to make sure they first understood the purpose of the routine. “Why do we share Roses and Thorns?” I asked them. We discussed the ways that sharing about our weekends makes us feel closer to our classmates and helps build community. We then translated the sentence frame: “My rose/ thorn from the weekend is ______.” We started listing verbs and vocabulary that they could use to describe the typical activities they did during their weekends. I immediately saw their faces light up in our small group space as they proclaimed their first full Rose and Thorn sentences.

When it came time to share the following Monday, however, I saw my newcomer students giggle bashfully when their turn came. I assured them they could share in Spanish, and I then had a volunteer from the class translate it. Finally, the newcomer students would repeat the English translation. With the suggestion of a colleague, I began starting my circles by having every student first turn and talk to share their Rose and Thorn idea with a partner. This gave all students a chance to practice what they would say, and the newcomer students were able to get help from a friend with English vocabulary and rehearse their sentence before saying it to the whole group.

Just a month into my inquiry cycle, all of my focal students went from saying “pass” when their turn came in the circle to consistently sharing a Rose and a Thorn.

In November, all my newcomer students were sharing in Spanish. To encourage the transition to English, I put sentence frames on the board, and crafted sentence patterning charts with the whole group to brainstorm subjects, nouns, verbs, and prepositional phrases they might want to use. In December, two of my focal students were sharing in Spanish and two were sharing in English. When we ended in-person school in March, all my newcomer students were sharing sentences in English. Over the course of the year, the students went from starting with the English frame and finishing with Spanish (e.g. “My rose from the weekend is fui al parque”) to English sentences missing verbs (“My rose from the weekend is Walmart”) to sharing full sentences in English (“My rose from the weekend is I played with my brother.”) Each week, I watched as they took a deep breath and carefully enunciated each word of their statement, then blush with pride when they finished. I also noticed the rest of the class take note of their risk taking and react with impressed expressions as their classmates’s English skills expanded. With this first step into feeling comfortable participating, I watched as my newcomer students’ confidence grew across subject areas and they raised their hands to participate more in math, science, and literature discussions.

With the help of additional scaffolds and consistent practice, the students’ writing also developed significantly over the course of my inquiry cycle. Their sentences were clearer and their spelling of high frequency words improved. I followed up this independent writing extension work with small group meetings to discuss their writing, and I provided more consistent spelling resources, such as personal spelling dictionaries, for each student.

As my inquiry cycle progressed, I noticed all focal students’s confidence and willingness to participate grew. A colleague in Lead by Learning noted that based on the writing, she could infer that the kids were happy to do the work, cared about it, and clearly felt they had something to say. In March, I started to feel like these students were ready for more challenging work and I wanted to shift my focus to supporting them with more academic writing. Watching my students quickly become so much more enthused to share and write was very rewarding, and showed me the far-reaching impacts of just a little additional attention, planning, and support.

I am still wondering about more ways of scaffolding academic writing for newcomers. Going forward, I want to get more ideas for how to gradually increase rigor in writing for newcomers without making the assignment so hard that they are frustrated and end up relying on copying a mentor text. How do we keep writing tasks in the zone of proximal development- challenging enough for students to know they are learning, but not so hard that they feel overwhelmed?

As a learner, I really appreciated the guiding questions we used in our Lead by Learning discussions: “What are you hoping will happen?” “What might be getting in the way?” “If you were wildly successful, what would you see?” These questions all helped me shift my thinking and focus on ways of setting my students up for success. By paying specific attention to their participation in the community circle setting, I was able to collect data on my newcomers’s confidence levels and their willingness to take risks, which directly informed my teaching. It made me more attuned to the skills and vocabulary my students needed in order to effectively participate, and reinforced my commitment to creating a safe learning environment in which all learners feel confident enough to take risks.

Mia Kleven is a third grade teacher who was born and raised in the Bay Area. After graduating from UC Berkeley, she fell in love with teaching elementary schoolers through her work as an AmeriCorps member with the literacy intervention program Reading Partners. She returned to UC Berkeley for her teaching credential and MA in Education, and has been teaching third grade at Bridges Academy at Melrose since 2016. When she is not teaching, she enjoys hiking, yoga, cooking, and snuggling with her cat.