Explorations in Tier II Vocabulary Instruction

As an English Language Development teacher, I want to empower students to understand how English works. In service of this goal, my students and I embarked on a year-long prefix-based vocabulary study to increase their Tier II vocabularies (high-frequency words used across disciplines). My interest in vocabulary instruction had piqued due to some recent learnings. First, reading comprehension is largely a product of the ability to decode text and vocabulary size. Second, vocabulary development by exposure and osmosis hits a ceiling around the 5th / 6th-grade level; all my students were middle schoolers meaning they were about to hit or had already hit this ceiling. And, finally, researcher Andrew Biemiller posits that vocabulary development is exponential. I reasoned that if students learned prefixes and how they functioned as building blocks of language, they would be better able to capitalize on this exponential growth, and, by extension, their reading comprehension would improve.

I decided that to show mastery of one of our weekly prefix-based vocabulary lists, a student would need to be able to do three things independently on a quiz:

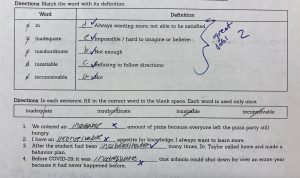

- Use context clues to fill in blanks in cloze sentences. A cloze sentence is one with a blank for a vocabulary word and enough context clues to determine the word that should fill in the blank

- Write original sentences with our vocabulary words that demonstrate an understanding of the word and correct syntax

- Define an unfamiliar word by breaking it into its prefix and base (e.g. unkind —> un = not, kind = nice, unkind = not nice)

Initially, I thought that if I explicitly taught a prefix and four accompanying words, gave students a day of dedicated practice, and had students make flashcards that they studied for five minutes every day, they would be able to show mastery. However, my first round of quiz data was disappointing and revealed my faulty assumptions. My focal students, two students at the intersection of language development and learning difference, got nearly every cloze sentence wrong and never even attempted the section of the quiz where they were supposed to write sentences with our target vocab words.

Based on my data, I knew I needed to make shifts in my practice. I learned from researcher and author Pauline Gibbons that students need at least 12-15 exposures to a new word before it might be cemented in their vocabulary. I had assumed that studying the flashcards counted as exposures, but now I realized that these exposures were all receptive (unproductive). So, I hypothesized that students needed more varied and rigorous exposures that required them to produce the language. I decided to implement a daily collaborative warm-up where, using their vocabulary list or flashcards, students worked in partners to complete the following four practices prior to the quiz:

- Picture and word relation: Using a word bank and four pictures students matched each word to an image and explained why the two were related

- Cloze sentences with explanations: Using cloze sentences similar to the quiz, students had to figure out which word completed the sentence and explain their reasoning for the selection.

- Sentence stem practice: Using a provided sentence stem students completed the sentence with the target word.

- Original sentence writing: With the support of a word bank, students practiced writing original sentences.

I hoped that these tasks would offer various access points to produce the prefix and vocab words and better support success on the quiz since several of these tasks mirrored the quiz. I also intentionally sequenced these activities so that the level of rigor and independence increased as the quiz approached. Furthermore, I emphasized that students should work collaboratively so that they were saying and hearing the words multiple times.

My next couple rounds of quiz data showed both growth in my focal students and a need to continue tinkering with my instructional routine. When asked to write a sentence with the word “abduct”, one focal student wrote: “I think abduct mean is to take away someone.” Another week, my other focal student produced the following sentence with our word “translucent”: “the window translucent because is clear.” While I was pleased that they were producing more original language, they were still not meeting my most important indicator of success because they were not writing an original and syntactically correct sentence with the target word.

At this point, I was feeling very stuck. I knew I needed to continue to iterate, but I had “teacher’s block.” Luckily, our next Lead by Learning assignment was to interview our focal students. Through that learning partnership conversation, I discovered that my focal students thought the most helpful vocab practices were making flashcards and connecting the words to images. I also learned from them that they weren’t writing sentences because they often didn’t know what to write about.

So, I started to brainstorm how I could amplify the practice where students connected the vocabulary words to a picture. I also wondered how I could support my students’ syntax since my focal students seemed to know what the words meant, but were struggling to use them correctly. I kept the cloze sentences and sentence stems from the previous weekly routine, and replaced the other practices with the following strategies:

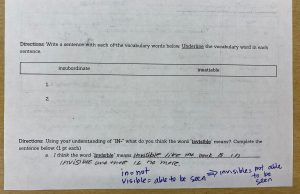

- Analyzing whether our vocab word was functioning as an adjective / describing word or verb/action word (our vocab lists focused on adjectives and verbs)

- Revising a sentence with a given vocab word

- Connecting each word to a picture and then writing a sentence about the picture using the vocab word

I hoped that analyzing how the words functioned in example sentences and revising sentences using the vocabulary words might help them write with proper syntax. I also hoped that giving them an image to write about would alleviate their writer’s block.

After a conversation with my Lead by Learning coach, I also decided to change the quiz. I had been hesitant to change the quiz because I didn’t want students to get confused by new directions or doubt my expertise, but, through that coaching conversation, I realized that the way the quiz was organized was not supporting my students in reaching my indicators for success. I moved the portion of the quiz where students write their own sentences to the front since that was the data I was most interested in.

The data for the original sentences were exciting.

After this shift, I saw even more growth! Each focal student was able to correctly match the vocab words to its image which indicates they knew the meaning of each word. They were also both able to write syntactically correct sentences. While the data in terms of their ability to meet the other two indicators of success was more varied, I still saw this as extreme growth from where they started.

After this shift, I saw even more growth! Each focal student was able to correctly match the vocab words to its image which indicates they knew the meaning of each word. They were also both able to write syntactically correct sentences. While the data in terms of their ability to meet the other two indicators of success was more varied, I still saw this as extreme growth from where they started.

As I reflect back on the year, my biggest takeaways from this inquiry are:

- When I feel stuck about my next instructional move, talk to my students! Ask them what’s working and what isn’t, and focus instructional iterations to amplify what’s working!

- While students need many exposures to a new word to truly learn it, those exposures need to be varied through multiple modalities and require them to produce the word orally and in writing

- Giving students something to write about reduces the cognitive load of generating the “what” and lets them focus on the linguistic load of actually producing writing with the target language

Despite all the growth in my students and my practice, I’m still wondering how to get my students to organically use more Tier II words when they speak and write. I haven’t been able to link our vocabulary study to increased vocabulary more generally or to higher reading comprehension / scores. But, those are questions for future inquiry!

Shelley Goulder currently works as a middle school English Language Development (ELD) teacher at Madison Park Upper, a 6-12 school in OUSD. In addition to teaching Humanities, Reading Intervention, and ELD in OUSD for the past ten years, she has also supported students and educators through inquiry work, coaching, facilitating grade level teams, and coordinating outdoors trips. Outside the classroom, she enjoys being in the mountains, snuggling with her dog, reading, and cooking.

Shelley Goulder currently works as a middle school English Language Development (ELD) teacher at Madison Park Upper, a 6-12 school in OUSD. In addition to teaching Humanities, Reading Intervention, and ELD in OUSD for the past ten years, she has also supported students and educators through inquiry work, coaching, facilitating grade level teams, and coordinating outdoors trips. Outside the classroom, she enjoys being in the mountains, snuggling with her dog, reading, and cooking.