Little Tweaks, Big Impacts: Moving Students Toward Strong Written Analysis

— By Eva Marie Oliver

I had just handed out grades and comments for my eighth-grade Humanities students’ first “assertion” paragraphs of the school year. After they looked them over, I asked each student to set an intentional, specific writing goal. In my cohort of 31 students, 25 decided that they needed to work on analysis. As one student put it, analysis is “where you prove your point, and I don’t really feel like I’m proving mine. So I need to get better.”

My teaching partner, Shelley Goulder, and I could not agree more – our students were struggling with analysis. We chose to focus our Mills Teacher Scholars inquiry on supporting students to write stronger, more coherent analysis in response to text. As always with the Mills Teacher Scholars inquiry process, we began by looking at the work of two students who were most skillfully doing “the thing” that we were looking for. Through careful evaluation of their writing, we were able to come up with an answer to a question that plagues many teachers: “What is good analysis?” Together, we arrived at the following indicators of success:

Within successful written analysis, there is:

- An accurate paraphrase of the quote

- Mention of at least one high-leverage word or phrase from the quote itself and relevant interpretation or significance of that word or phrase

- Mention of the greater significance of the quote as it connects to the claim

- Clear, traceable logic between these steps

We hoped that through better understanding these indicators, we could help all of our students turn their brilliant ideas into compelling, convincing written analysis. Thus began a humbling, yearlong process of tweaking and adapting our instruction until we arrived at an iteration where we actually began to successfully teach our students to analyze.

Our First Try: Close Reading, Guided by Question and Claim

In our first try at adapting our instruction to meet our students’ needs, we decided to modify our close reading practice during a unit on Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass. We created a tool that supported students to write an assertion paragraph around a particular quote and claim, asking them to be sure to mention at least one high-leverage word or phrase from the quote in their analysis. (We defined “high-leverage” words and phrases as small pieces of a quote that carry important interpretive and/or analytical weight. In other words, these are the words and phrases that give a quote its meaning and significance.)

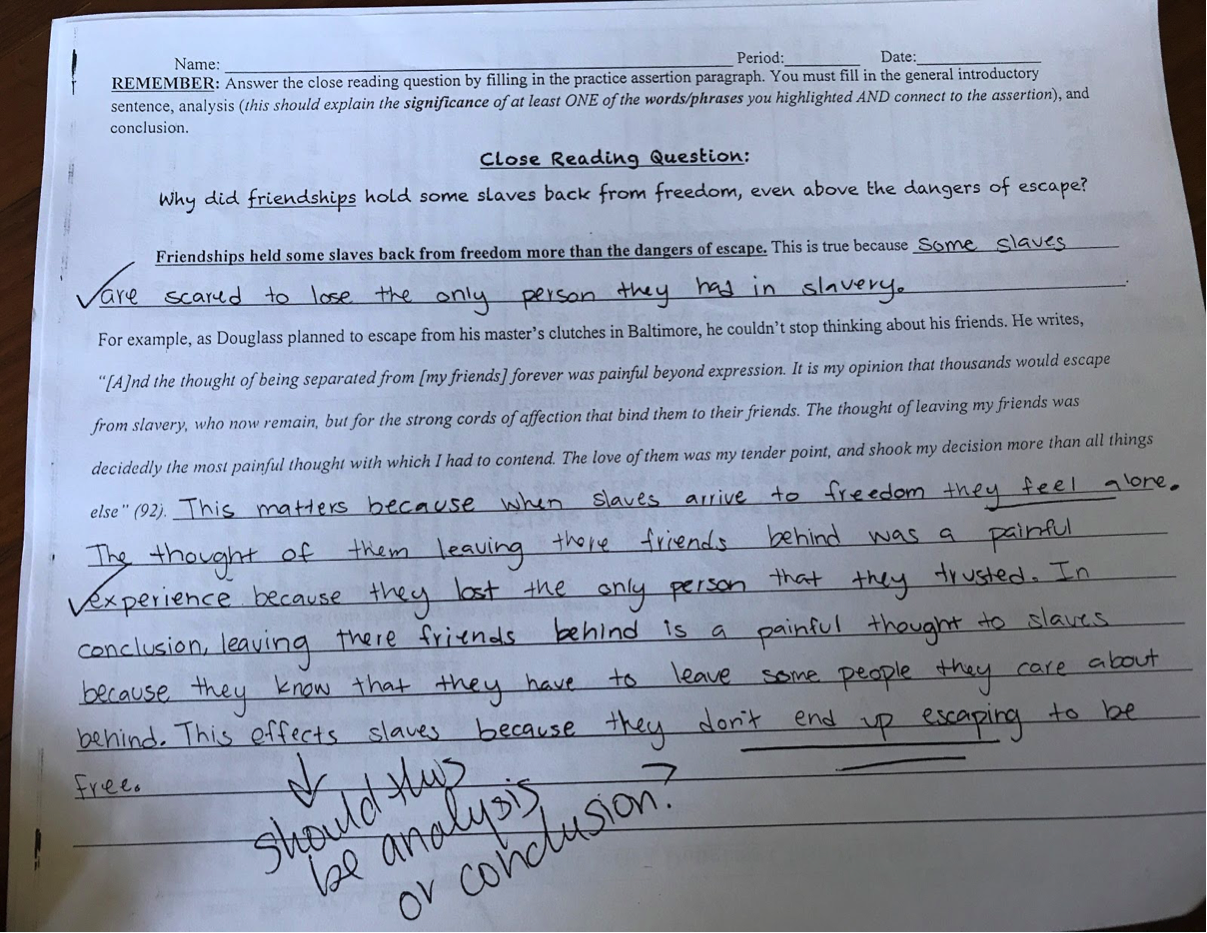

We soon learned that this adaptation was not enough for one of our focal students, Katrina, who wrote an assertion paragraph in response to the question: Why did friendships hold some slaves back from freedom, even above the dangers of escape?

While Katrina expressed that some slaves ended up choosing friendships over the possibility of freedom, her paraphrase of the quote was stunted and some of her best thinking, where she really connected the quote to her claim, ended up in her conclusion. Also, Katrina’s high-leverage word, “painful,” was not as high-leverage as others and did not give her much to dissect and interpret. Choosing a phrase like “tender point” might have allowed her to go into more of the nuances around the tension of slaves who dismissed the thought of escape because of their friendships.

In looking at Katrina’s and other focal students’ writing at this point in our inquiry, we realized that while giving students a claim helped them at least superficially interpret the quote, it did not help them latch onto key words or the quote’s deeper significance.

Trying Again: POWER Quote Practice v.1

Since our first modification to our instruction resulted in students like Katrina still struggling with all four indicators of success, we tried again. This time, we tried to further scaffold the process. In POWER Quote Practice v.1, we broke the paragraph apart to make the analysis process more linear, following these five steps:

- Closely read a powerful quote and highlight several high-leverage words

- Summarize or translate the quote into your own words

- Interpret the significance of one of your high-leverage words or phrases

- Choose which claim you believe the quote directly supports

- Combine these steps in writing an analysis paragraph

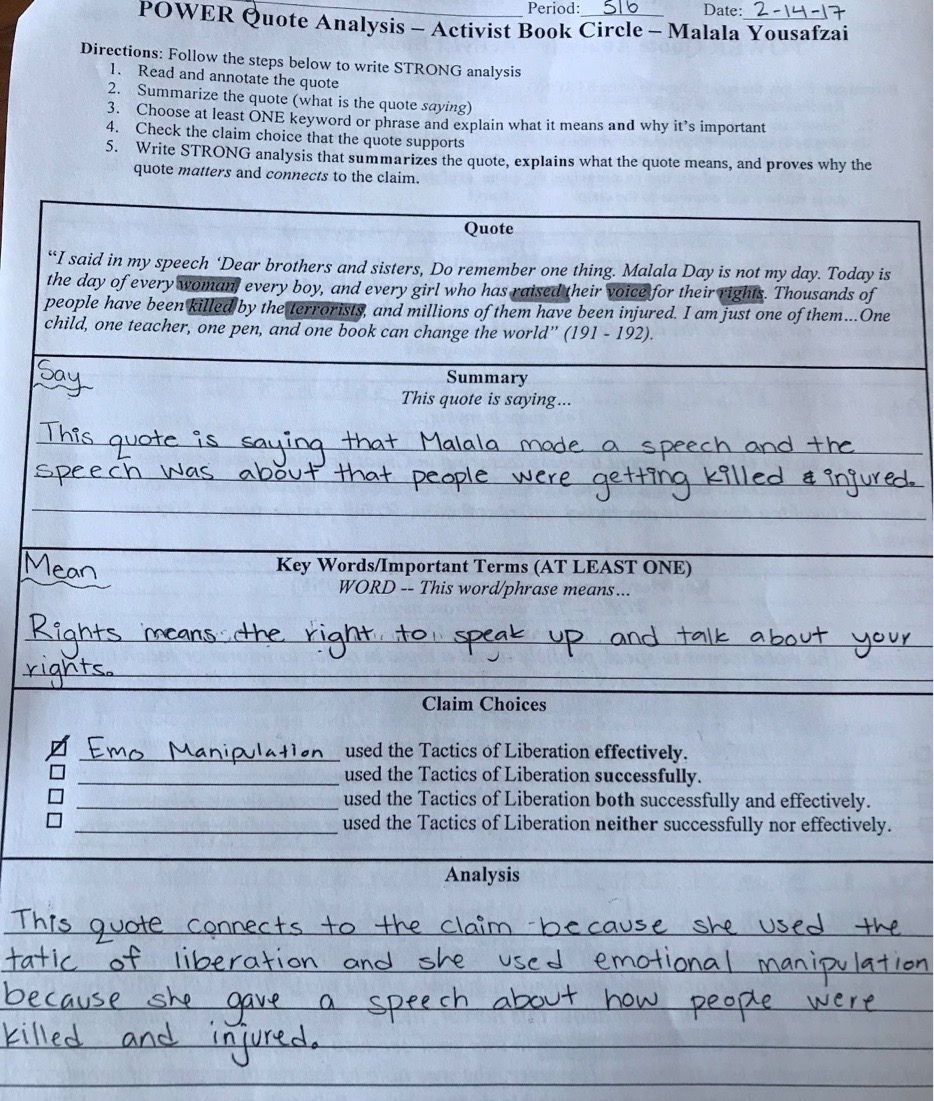

Despite our efforts, this interaction was a further step backward for Katrina, as we saw when she analyzed a text from Malala Yousafzai:

My teaching partner and I were worried. This scaffold seemed to move Katrina further away from her goal of writing convincing analysis. First, Katrina’s summary of the quote is inaccurate. While Malala did mention that people are getting injured and killed, that understanding does not encompass the essence of what the quote is about. Second, Katrina’s definition of her high-leverage word, “rights,” is confusing. She uses her high-leverage word twice in her own interpretation, making it hard to know if she truly understands its meaning. Third, in the analysis section, Katrina does correctly identify that Malala is using emotional manipulation, but she not address the second part of the claim about Malala’s effectiveness or success in her use of that Tactic of Liberation.

This instructional strategy did not help Katrina arrive at an accurate summary of the quote nor a relevant interpretation of her high-leverage word. More problematic, this strategy did not help Katrina and other students see that all of these steps needed to be present in the analysis in order to fully prove their claims. What next?

We Keep Trying: POWER Quote Practice v.2

Although there seemed to be a lot of issues with v.1, my teaching partner and I chose to make one small change to the tool before abandoning it altogether: we gave students the high-leverage word or phrase that we believed would open up their access to the quote and enhance their analysis.

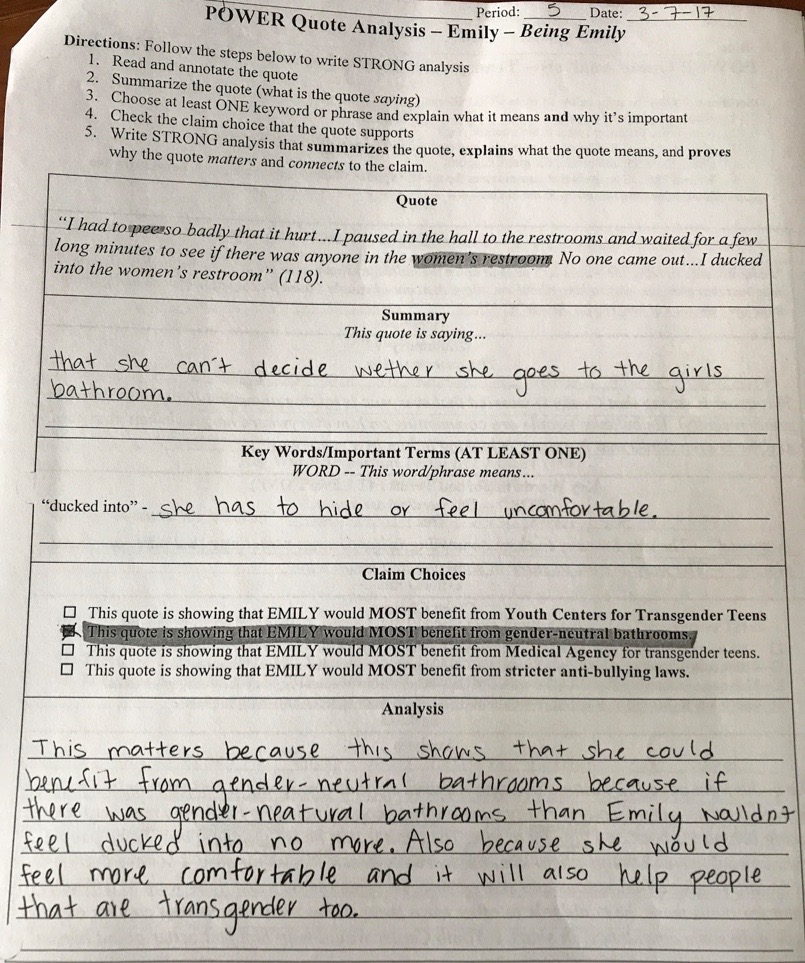

This time, we saw significant growth in Katrina’s work, as when she responded to a transgender person’s dilemma over choosing between gender-specific bathrooms:

We saw two important improvements in this iteration. To begin, while Katrina’s summary of the quote is still a little superficial, her definition of the high-leverage phrase “ducked into” enhances the summary because it speaks to the discomfort that the protagonist feels in the gender-specific restrooms. So, we believe that the opportunity to define that specific phrase boosted Katrina’s comprehension. Then, Katrina even uses the high-leverage phrase in her analysis to prove that her protagonist needs gender-neutral bathrooms to help her feel more comfortable.

After this third instructional modification, we saw that providing students with high-leverage words and phrases not only boosts their comprehension of the quote – because they know that they should seek to understand that piece of the quote – but it also models the kinds of words and phrases that are “worthy” of interpretative work.

We Continue to Practice with POWER Quote Practice v.2

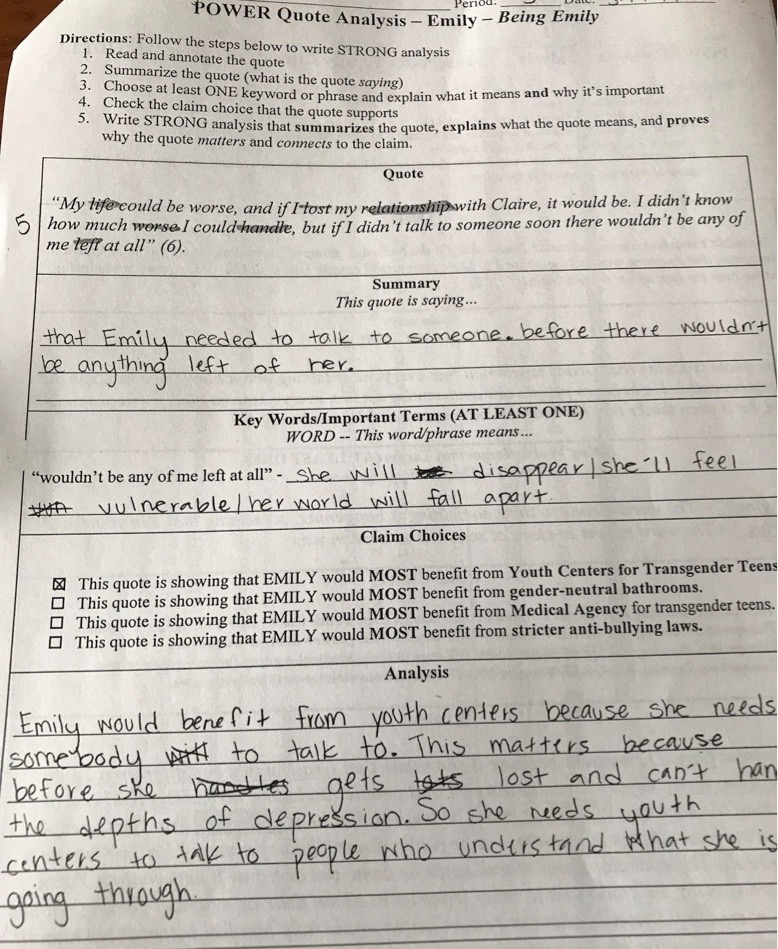

My teaching partner continued to have students practice with v.2 while giving feedback on our fourth indicator of success (clear, traceable logic between steps). Happily, we continued to see more success, especially around meaningful interpretation of the high-leverage words and phrases.

Here, notably, we see that Katrina’s definition of her high-leverage phrase is nuanced; she even offers three different possible interpretations that are all relevant and meaningful. Furthermore, she builds on those interpretations in her analysis in order to prove that her protagonist needs youth centers to not fall into “the depths of depression.” Finally, success! This was exactly the kind of analytical work that we wanted to see our students engage in.

Conclusion and Future Wonderings

Through this inquiry, my teaching partner and I realized how much a comprehension breakdown around a chunk of text can impact a student’s ability to write analytically. To combat this problem, we wanted students who were reading below grade level to have access to tools that allowed them to unpack small chunks of text (i.e. quotes) in order to boost their analytical skills, while simultaneously working on their overall reading comprehension. We found that providing high-leverage words and phrases addressed both of these concerns. The strategy gave students the key to open up an important part of the quote and offer their own interpretation. While they may not fully comprehend the whole passage, they had something to write about in their analysis because they understood a crucial and relevant piece.

In the upcoming school year, I hope to learn more about whether providing high-leverage words and phrases truly acts as effective modelling for students. By this I mean, by repeatedly encountering and evaluating the words and phrases that I pick, are my students empowered to find their own AND use them effectively in their analysis?

Eva Marie Oliver has been teaching English Language Arts and Humanities at Life Academy of Health and Bioscience in Oakland, CA, since January 2011. After earning her BA in English at Sonoma State University (2010) and her credential and MA in Education through UC Berkeley’s MUSE program (2012), Eva has been proud to contribute to the social-justice-oriented and transformative learning space that is Life Academy. Working with Mills Teacher Scholars and the Bay Area Writing Project has enriched her professional experience as an educator in the Bay Area. If not in the classroom, Eva can be found reading, practicing yoga, hiking, or weight lifting