Collaborative Inquiry Leads to Powerful Changes in Practice

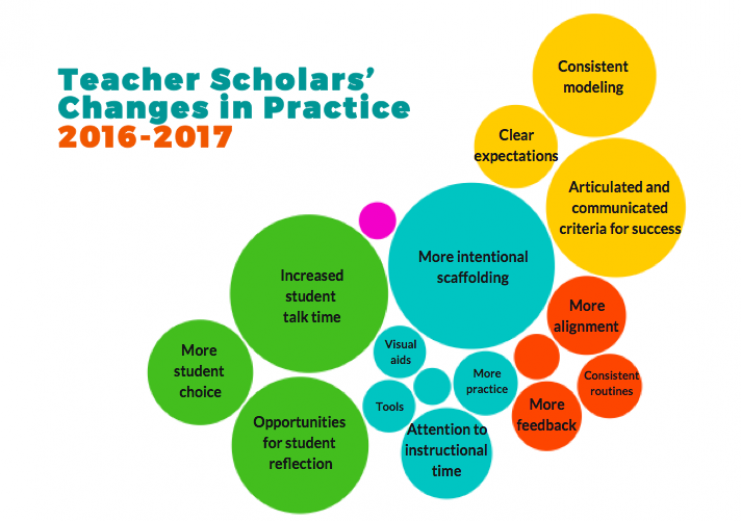

In 2016-17, our teacher scholars named changing their practice in four powerful ways as a result of learning through collaborative inquiry.

- Becoming more student centered by supporting student talk, choice and reflection;

- Communicating learning expectations explicitly with checklists, rubrics and models;

- Rethinking the supports provided to scaffold student learning, like incorporating visuals, graphic organizers, additional time, and practice opportunities;

- Planning new routines to emphasize consistency, align to curriculum, break down steps, and provide moments of feedback.

These changes in practice positively impacted student outcomes. Stories from four of our teacher scholars’ classrooms bring this impact to life.

1. Becoming more student-centered

Mills Teacher Scholar Travlyn Langendorff observed that her 11th-grade American Literature students were not engaging in “substantive” class discussions. Through collaborative inquiry, she experimented with different ways to support students in talking to each other, instead of just to the teacher. As her understanding grew, she provided students with sentence stems, practice time, and leadership opportunities during conversations about literature. As a result, her students showed improvement by participating more regularly, responding directly to each other, and using rephrasing strategies to more clearly their articulate ideas.

2. Communicating learning expectations

Mills Teacher Scholar William Juang struggled to support his students in diving into challenging assignments. Will reflects, “I discovered that in many instances students actually knew more than they showed on paper, largely because they did not understand what was expected of them for an assignment. In the course of my inquiry, I found rubrics to be effective tools that allowed me to spell out for students what my expectations were. Regularly using rubrics as an intervention, I was able to outline expectations to students on a physical document that they could reference at any point in their assignments. I proceeded to restructure my units such that I actually take the time to allow for students to understand the rubric and practice with it.” After investing time in coming to shared understandings with his students about their learning expectations, Will found that the quality of their written responses dramatically improved.

3. Rethinking the supports

Mills Teacher Scholar Anna Tom was new to teaching Kindergarten, and the systems she had developed for her 1st and 3rd graders weren’t helping her new Kindergarten students improve their writing. Through gathering and analyzing student learning data during collaborative inquiry, she understood that students at different stages of development needed different supports, or scaffolds, to help them grow. To scaffold students at the “labelling” stage, she allowed students to dictate and then trace over her transcription of the first sentence of their story, then encouraged them to continue on their own. As a result of this change in practice, Anna saw marked improvement: “My students did not all start at the same starting line, but with differentiated instruction they all finished our unit with 3-page booklets that they had excitedly used our checklist to revise and edit.”

4. Planning new routines

Mills Teacher Scholar Sara Oremland realized her students “didn’t seem to know what kind of information they needed to find to accomplish a research task.” In collaboration with MTS and colleagues, Sara interviewed proficient students, which led to a breakthrough: proficient student researchers “reframed the question in their own terms.” This led Sara to develop a new routine to support all students in reframing their research questions: the “KWH” chart. Like a “KWL” chart, the routine of completing a KWH chart asks students to anticipate their research, generating synonyms and related questions to interpret the question in students own terms. Sara changed her practice by planning a new routine to push all students to try the research reframing that her proficient students were modelling. Sara reflects: “The result was that we went from 70% finding not-that-great sources to 70% finding the kind of information I would want them to find. And the really proficient kids found way better sources than the proficient kids did the first time.”